On arrival to PAH Betty had a chest drain inserted and this was aimed at draining the fluid from her chest. Now here is the bit I never understood and I still struggle with it so please bear with me. The fluid that was drained off her chest was measured every hour and documented. In neonatal care the very tiniest of figures are significant and so this was a vital part of Betty’s treatment. Luckily, James as an engineer had a sound grasp of the mechanism at play and he kept a very close eye on the drain. He actually helped the doctors a couple of times when there had been some confusion with the drain. Chest drains in neonatal care are not common practice and so understandably the staff were a little unsure at times. This is not a criticism of the nursing team, they were and are the most magical wonderful humans alive, but this was just an unfamiliar procedure.

James explained to me that equal fluid was being put back into Betty via her many tubes, in the anticipation that she would begin to appropriately place the fluid around her body, out in her urine for example, and stop dumping it into her chest cavity (pleura).

Now a little note on how things run at PAH. Every week the doctor in charge of your baby changes. This is obviously for good reason, but it is unsettling to have a new doctor each week because I didn’t know if they would completely change the plan with Betty or if they would continue on the path that I had (sort of) got my head around.

Betty’s main doctor, the one that was in charge of her care overall, was a lady and for the sake of this blog I will refer to her as Dr F. Mum liked her, which was a good start! She had a kind face, genuine and she was on the ball. She had been fully briefed about Betty and on day one, she and the nurse for Betty that day took me and James into the room we were in on the ward (the family room that we slept in the first two nights). We all sat down. I remember their faces, they were serious but kind and empathetic. They were delivering information to us and it wasn’t good, but I can’t recall it and I am thankful for that blip in my memory. One thing I do remember though, is that Dr T from QAH trained Dr F, and I liked Dr T, he’d given me hope on the day Betty was born so anyone trained by him would be a skilled and knowledgeable Dr. After that conversation I don’t remember seeing Dr F for a while but I was happy that she would be kept up to date with Betty and would be making the big decisions. Dr F filled me with hope, she wanted Betty to get better, I could see that in her eyes, I have a good sense of people and their characteristics and this Dr was definitely a good egg.

As well as the fluid situation, Betty was also born in complete renal failure, another fact I learned after the event. Luckily, her organs were all fully formed and after two doses of Furosemide she was urinating well and her catheter was removed. This was progress, small, but it was positive.

On day two a team of geneticists came to see Betty. There were three of them and not to be judgemental, but if you imagine what a geneticist looks like, these guys were just that. They looked geeky, clever and didn’t have the same soft, calm persona as the other professionals. Nonetheless they were there to help provide us and the medics with answers. They had a camera and they took phots of Betty. Her face at different angles, her feet, chest, back, arms and hands. You name it, they photographed it. This is because babies born with hydrops often have a genetic condition which causes the fluid build up. Babies with hydrops also usually have a heart or lung condition which would cause the fluid to leak into the wrong compartments. I didn’t realise there were so many genetic conditions but there are and none of them are detected in the tests you have during pregnancy. I hadn’t heard of the conditions the doctors were talking about. I googled some of them and I wept. I started to grieve even more. I thought if Betty had a long term condition that she wouldn’t have a quality of life. How naïve I was. Since this, I have learned so much about the beautiful babies/children that have various genetic conditions, and they are all wonderful, loved, happy little people. But in my state of shock, I couldn’t comprehend a child that could be different to what is deemed ‘normal’. To me, it was another blow that I couldn’t take.

One genetic condition that was talked about a lot was Noonins syndrome. I had never heard of this but mum said straight away, ‘she doesn’t look like a Noonins baby’. I was curious and scared so I googled Noonins syndrome. I was frightened. I wanted ‘normality’ for Betty. However, I later learned that Noonins syndrome is not necessarily life limiting, it is a condition that people can live with and some people have it and don’t even know. I learned all of this much further down the line though. I remember one of the doctors saying that Betty had one feature in particular (on her body) that made him and the genetics team suspect Noonins. James was not phased in the slightest. He was accepting of all possibilities, as long as Betty would have a good quality of life, we could cope with any additional needs. I didn’t mention Noonins to any of the communications team (more of them later). I didn’t want them to ask questions or god forbid, google it and make assumptions, so I quietly tortured myself. The difficulty with this possible diagnosis was that Betty was still ever so swollen and so it was tricky for anyone to really see her features at all (facial and body feature/proportions can help to identify genetic conditions), if you would like to know more then please read (http://www.geneticdisordersuk.org/aboutgeneticdisorders). So I agreed to additional testing for this condition. I was told the results would take up to 6 weeks to come back (they actually took 3 months, not that I was counting…).

One doctor in particular had taken a real interest in Betty and I saw him one day researching hydrops and searching for other causes or conditions linked to it. The fact that Betty’s hydrops had evidently developed so late in the pregnancy was baffling to the professionals (and us). Usually hydrops is picked up at a 20 week scan and the prognosis tends to be poor. Hydrops is also difficult to detect for a novice sonographer and so it can be missed. I was lucky beyond all belief to have had Mr SG perform my scan as he recognised it instantly.

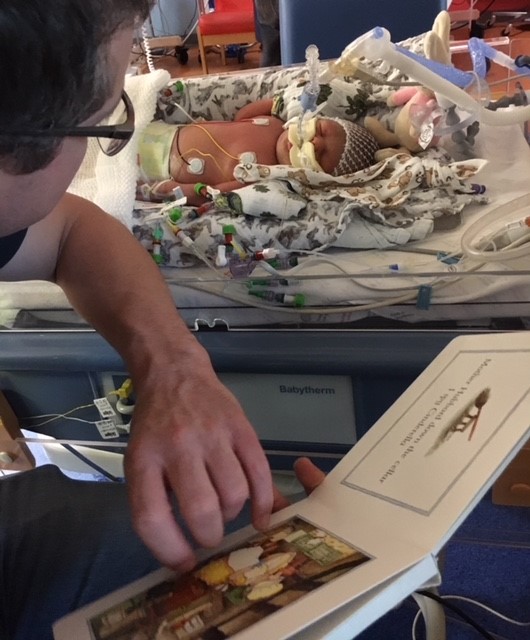

All the while this is happening, people are toing and froing from our little girls’ cot side, and all the time she has a chest drain in her right side, draining fluid constantly. The fluid keeps up its pace, draining almost equal measure to what is being pumped into her each day. James has his eye on the drain and is keeping tabs on it. He and the doctors discuss it in detail while I sit next to my little warrior, bottles attached to each boob and pump, pump, pump. Betty is still fully ventilated and paralysed by the drugs. My poor little sausage. I would talk to her, tell her how much I loved her, how much I wanted to cuddle her, hold her, take away all of her pain. Even going for a coffee would take a good ten minutes of telling her how much I loved her and whispering “I love you baby girl, be healthy, be strong, be happy”. I said sorry to her a lot. I failed her, albeit completely unknown, my body failed her completely and to this day, I blame myself. I didn’t drink alcohol or smoke or use drugs. I didn’t even take a paracetamol for a headache while pregnant. I ate well, I exercised regularly. But somehow, somewhere along the line my body let her down and I will forever place the blame for that on me. There is simply no one or nothing else I can blame. It is something I live with every day and although it has not gone away, it is getting a little easier to live with as I watch her grow and smile and play.

I look at her and I think, this didn’t happen to us, to you, surely not. But I dream it every night and I relive it every day and I am reminded that yes it did happen, and I am still trying to heal myself while growing my darling little sausage. (Betty is my ittle sausage!).

Recent Comments